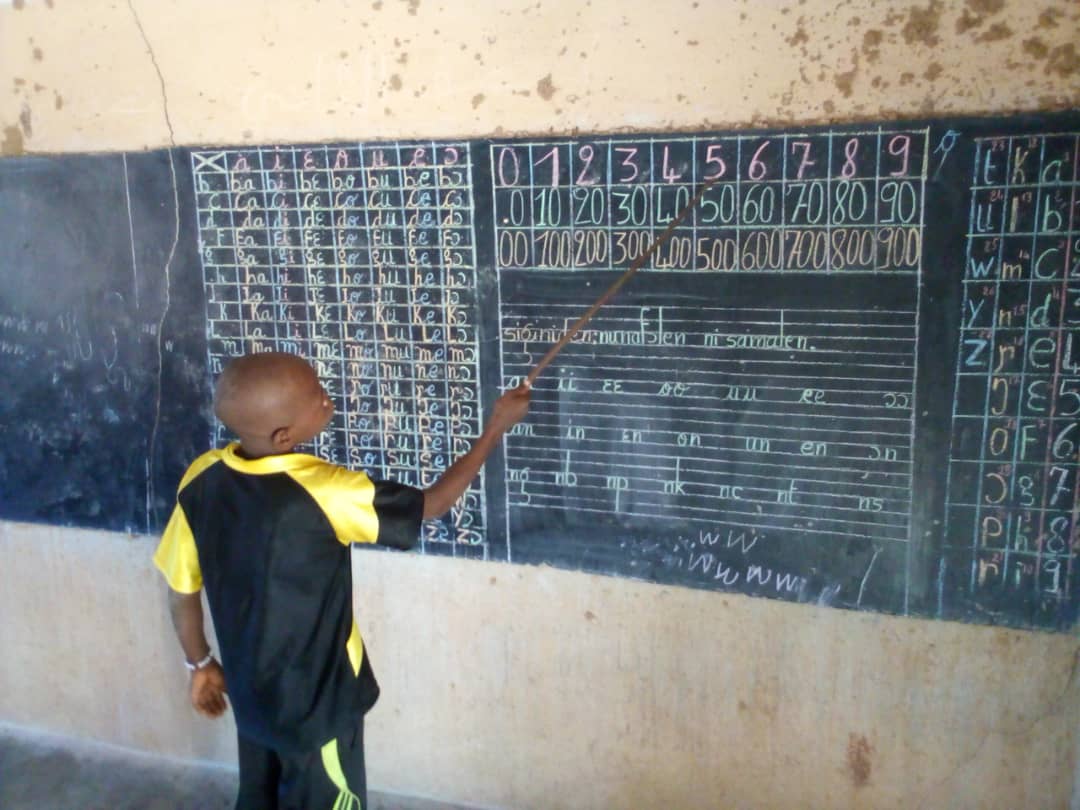

Those are the words of Noumoutieba Diarra, a former child worker who turned teacher and contributed to eliminating child labour in Ouroun, in the Bougouni region in Mali. This area is known for its gold-mining industry, a traditional activity, practiced in many communities in Mali. Many children were working on small scale informal gold panning sites and did not go to school. As a child Diarra had to interrupt his education, but thanks to his perseverance, now he is a proud teacher himself. “I knew it was via teaching that I could prevent others from having the same fate as me.”

Root causes of child labour

There is a range of social, economic and political factors responsible for the persistence of child labour in many countries. Contrary to what is often assumed and stated, poverty is in most cases not the decisive factor in pushing children into work and child labour is not vital to helping poor families survive. Research shows that children’s wages only contribute marginally to the family’s income.

There is a range of social, economic and political factors responsible for the persistence of child labour in many countries. Contrary to what is often assumed and stated, poverty is in most cases not the decisive factor in pushing children into work and child labour is not vital to helping poor families survive. Research shows that children’s wages only contribute marginally to the family’s income.

Sofie Ovaa, programme manager of the Work: No Child’s Business Alliance, explains: “Social norms and traditions, social exclusion and discrimination, and poor functioning education systems are key reasons why children are working and not attending school. The lack of decent work for adults and weak law enforcement by governments also contribute. Many children work in the informal sector, an area of economic activity that is largely invisible and unregulated by governments.”

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic the number of child labourers is increasing with millions. We know from previous crises that the longer children are out of school, the greater the risk that they do not return to school. Studies on the impact of the pandemic on children by UNICEF and Save the Children show that nearly 10 million children may never return to school.

Child Labour and education are inextricably linked

Providing access to education for all children is one of the most effective strategies for eradicating child labour. Education is a fundamental human right. All countries worldwide have ratified the UN and ILO conventions on children’s rights and child labour, and have laws on compulsory schooling. In principle this means that all children should be in school, everywhere.

Providing access to education for all children is one of the most effective strategies for eradicating child labour. Education is a fundamental human right. All countries worldwide have ratified the UN and ILO conventions on children’s rights and child labour, and have laws on compulsory schooling. In principle this means that all children should be in school, everywhere.

“But we all know that is not the reality”, says Trudy Kerperien, International Secretary of the General Union for Education (AOb). “Education is a large part of the solution in fighting against child labour. But it is at the same time part of the problem. An important reason is that we take education for granted. When a child is in school, we assume everything is okay. But school is more than just a word or a building. It is more than learning to count or read. Education is preparing children for a future. And to be able to this, we need quality education. When the quality of education is not good or not good enough, we see worldwide that children drop out. And once out, the step to start working is easy.”

Improving access to education is one thing, to retain children in school is another. It remains important to improve the quality of education. This means working on quality teaching (such as improving initial teacher training, continuous professional development, but also adequate salaries), on quality tools for teaching and learning (including appropriate curricula and inclusive teaching and learning materials and resources), as well as on quality environments (that should be attractive, comfortable, safe and secure, with the appropriate facilities). “To achieve this, an issue so entangled with social, economic, legal and political issues, we also need to involve and engage with other relevant actors. We need support from governments, on all levels. Local, national and international”, pleads Kerperien.

Urgency for investment

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, education systems are facing a devastating crisis in public financing. UNESCO estimates at least $210 billion will be cut from education budgets next year simply because of declines in GDP. This will undoubtedly have an impact on the return of children to school and the quality of learning if they do.

David Archer, Head of Programme Development at ActionAid, makes a strong plea for the urgency for investments to ensure that all children can fully enjoy their right to good quality education. “We need to promote financing for public education in the fall-out of the Covid pandemic. This requires first to defend the share of the budget spent on education. To increase the size of the budget we need tax justice. And of course, the close monitoring of spending is essential.” To build long-term sustainable education systems that will be adequately financed, countries need to use all fiscal space available by mobilizing domestic resources. They may also need external resources to cope with the crisis and maintain a sustainable level of debt.

Archer also emphasizes the need for CSO’s, teacher associations and women organizations to collaborate in a broad movement to plea for tax justice and a strong public sector. “Lobbying for education should not compete with lobbying for health or other public services.” The Covid-19 crisis is catastrophic but can also be used as the momentum to lobby for a new economic order and more progressive thinking on public spending as a means for stability. The influence of institutions like IMF, committed to austerity measures instead of public spending, is in that way harming. “I would very much like to see a collective statement pushing for debt suspensions for the benefit of a strong public sector,” he concludes. “If you are serious about education and child labour, you need to be serious about the financing.”

Archer also emphasizes the need for CSO’s, teacher associations and women organizations to collaborate in a broad movement to plea for tax justice and a strong public sector. “Lobbying for education should not compete with lobbying for health or other public services.” The Covid-19 crisis is catastrophic but can also be used as the momentum to lobby for a new economic order and more progressive thinking on public spending as a means for stability. The influence of institutions like IMF, committed to austerity measures instead of public spending, is in that way harming. “I would very much like to see a collective statement pushing for debt suspensions for the benefit of a strong public sector,” he concludes. “If you are serious about education and child labour, you need to be serious about the financing.”

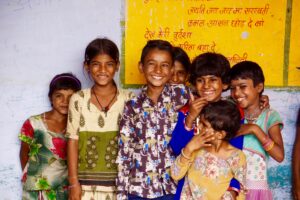

Good practices from India

The Indian MV Foundation works on the development, implementation and strengthening of child labour free zones. Venkat Reddy from the MV Foundation has been active in combating child labour in India since the 1990s. “In a child labour free zone, no distinction is made between different forms of child labour; every child is entitled to education. It is our experience that the elimination of child labour is possible.” Teachers, local authorities, village leaders, employers, parents and children in these zones work together to get children out of work and into school. Child labour is no longer accepted because all stakeholders gradually built up the shared conviction that no child should work – every child must be in school. Venkat explains: “Child labour does not reduce poverty in a family. It actually leads to more poverty. In our experience, parents are motivated to send their kids to school. They do not require income generation, but good, accessible and quality education for their children. You cannot and should not shift the responsibility to the parents. We see for example that there are more enrolments than places in school, which makes it very difficult for parents to find a school near their home. Even if they really want to.”

The Indian MV Foundation works on the development, implementation and strengthening of child labour free zones. Venkat Reddy from the MV Foundation has been active in combating child labour in India since the 1990s. “In a child labour free zone, no distinction is made between different forms of child labour; every child is entitled to education. It is our experience that the elimination of child labour is possible.” Teachers, local authorities, village leaders, employers, parents and children in these zones work together to get children out of work and into school. Child labour is no longer accepted because all stakeholders gradually built up the shared conviction that no child should work – every child must be in school. Venkat explains: “Child labour does not reduce poverty in a family. It actually leads to more poverty. In our experience, parents are motivated to send their kids to school. They do not require income generation, but good, accessible and quality education for their children. You cannot and should not shift the responsibility to the parents. We see for example that there are more enrolments than places in school, which makes it very difficult for parents to find a school near their home. Even if they really want to.”

*********************

Webinar on quality education, stakeholder cooperation & advocacy

On 13 April Global Campaign for Education Netherlands and Work: No Child’s Business organised a webinar on education and child labour. Different topics have been discussed, with impactful examples and recommendations.

Pillars of quality education

It requires investment in different pillars to build quality education. Quality teaching, based on good teacher training, initial and permanent, including learning about child labour, as well as learning to monitor child wellbeing and referral to other actors such as child protection organisations or health care. A stable life for teachers based on a decent salary is crucial. Quality tools, based on an inclusive and child centred pedagogy. And a quality teaching and learning environment, that is safe and transparent, and where barriers for admission are removed. Robert Gunsinze, programme manager of UNATU – the Ugandan Teachers Union -, described how they worked with teachers within the communities to improve the quality of education. “We have been working in the Western Nile region since 2015. To ensure that children attended and stayed in school, we carried out trainings to train teachers. We trained them in child friendly learning methods and banned corporal punishment in the classrooms. The teachers were also trained in menstrual hygiene management, because we knew this was a big obstacle for girls to attend classes. We also worked on improving the school environment. Toys and music instruments were bought, and together with the teachers we have set up theatre and sports classes. Through these activities we have safe and gender responsive schools, with great improvement in enrolment and attendance.”

Cooperation with stakeholders

It is essential to work with all other stakeholders in an area. By bringing everyone together it is possible to create a supportive and encouraging environment for the children. This also includes social dialogue spaces, where all stakeholders at local level are included. Fanta Kone, programme coordinator Work: No Child’s Business in Mali gives an example that shows the impact of cooperation at a local level. “We have set up a community dialogue in a village in the Bougouni area. We brought local chiefs together with the community and local stakeholders like schoolteachers. As a result, the chiefs took the decision to ban child labour. This decision immediately brought back many working children to school.”

Advocacy for investements

A third discussion took place on how to adapt advocacy strategies within the current covid crisis. There is an urgent need to keep promoting the importance of formal, full-time, and quality education for all children and to fight for sustainable investment in education. We need to create momentum and build a coalition, as broad as possible, with local, national, and international actors to respond this high sense of urgency. Monica Banerjee, programmes director at ICCO India and country lead for WNCB, gives fuel to the discussion with interesting examples from the Indian context. “Also in India we see a decrease in the budget allocation for education. Education activists and child rights activists collaborated to locate the position of child labour in the National Education Policy of the Indian government”, she says. “But so far this focus in the new policy has still not been taken on board; in conjunction with the relaxed labour laws in India this is very detrimental to the child involved in labour”. More positive is that some states and the civil society have initiated Multi Activity Centres for children amidst the lockdown. And through media channels publicity is given to the impacts on children rights.

The webinar has been recorded. Are you interested in watching one of the break-out sessions or the plenary session? Please contact info@globalcampaignforeducation.nl