Bridge classes & apprenticeships

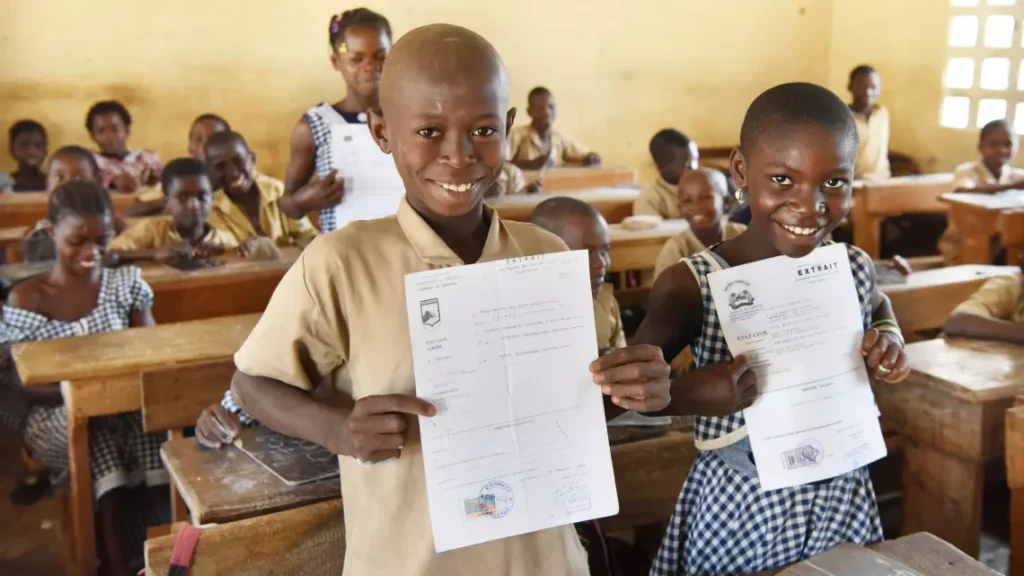

Ambroise Kla is project manager for Save the Children in Côte d’Ivoire. He emphasises how, during the four years of implementing the WNCB programme, access to education for children at risk or in child labour situations was facilitated by establishing 100 bridge classes, accommodating approximately 2,000 children. “Out of these, around 1,600 children were actually admitted to the formal education system through one of the bridge classes”, he says.

Moreover, the strong collaboration with regional education authorities like DRENA (DRENA is a decentralised structure of the Ministry of National Education and Literacy that is in charge of education in a region), led to 10 bridge classes now being incorporated into the formal education system. As bridge classes become formalised, they have access to more funding and materials, bringing the formal education system into areas that were previously inaccessible or overlooked. For the time being, the remaining 90 bridge classes continue operating with the support of the community members.

So, what do the bridge classes look like in the context of Côte d’Ivoire? How did Ambroise and his colleagues go about in the process of setting them up? And, how did they optimise the cooperation with authorities?

Second chance schools

“In our programme areas, we often describe the bridge classes as our ‘second chance schools’”, says Ambroise. “They are specifically designed for children, between the ages of 9 to 14 years, who dropped out of school at the beginning of their education. The bridge classes offer these children the possibility to catch up on the school years that they have missed. The programme offers an accelerated curriculum through which bridge class students can do two grades in one year.”

“You might think that combining multiple grades in one year, means that the bridge classes are more difficult than normal classes”, Ambroise adds. “However, because of the fact that the bridge class children are usually much older, they are also more capable of assimilating everything that they need to learn. They can handle more topics at the same time and they can learn faster.”

Well-defined implementation process

Bridge classes have been set up in various localities under different circumstances. But by following a well-defined approach, repeating the same strategy and the same steps, Save the Children has defined an implementation process which has become transparent and straightforward to replicate. This process begins with presenting the project to the administrative and educational authorities, raising community awareness, and identifying the children who need bridge class education.

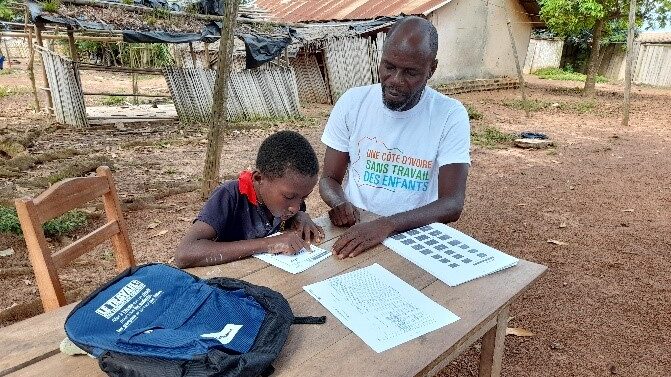

Subsequent steps include the recruitment and training of voluntary facilitators who will become bridge class teachers. These facilitators represent a potential pool of professionals who after further training and qualification can be deployed to formal schools to address the shortage of teachers. Just like these facilitators, teachers in formal schools will receive training to facilitate the integration of learners from bridge classes into formal schools. These training sessions are combined with awareness sessions on the role of teachers and students in eliminating child labour.

Cooperating with authorities

Crucial in all steps of the implementation process is the cooperation with local and central education authorities. The community volunteers are selected by educational counsellors from the national education system and are then trained by WNCB teams. “By passing the required exams, the authorities will recognise them officially as teachers for the bridge classes”, Ambroise explains. “This is an important and encouraging signal, to our communities as well as to our teacher staff themselves.”

But it is also in identifying the children, that the WNCB programme is supported by the Ministry of Education. “It is on the basis of the information from central databases that we have a first idea of which children are eligible for bridge class education”, Ambroise specifies. “With that data we go to the local community, and together with the community members we decide on the final selection of children for the bridge classes. This cooperation between national and local authorities, and the communities, that is one of the main reasons for the bridge classes approach to be successful. We work together.”

Boosting literacy

Another successful element in the bridge class approach is the application of the Literacy Boost method. The Literacy Boost method, and the similar Numeracy Boost method, are two approaches that were designed specifically by Save the Children. They are used in educational interventions to help make the teaching and learning of reading and math easier for teachers and pupils, using games and the pupils’ native language. The aim is to make lessons more attractive through playful means, and to foster a literate, digital environment in the classroom.

However, in the context of the WNCB programme in Côte d’Ivoire, the Literacy Boost programme is not only focusing on teachers, but even more on parents and communities to support children with increasing their literacy learning. “For this approach to be successful, even more cooperation is required”, Ambroise explains. “Teachers need to be trained, parents need to become involved, and community members need to support, for example by creating ‘reading corners’ and by making a variety of reading materials available.”

Apprenticeships

In addition to the bridge classes a collaborative framework for apprenticeship for youth was set up in cooperation with the central and regional government departments in charge of apprenticeship and professional integration, and the regional chamber of trades. The apprenticeship programme was aimed primarily at young people living in the most isolated areas. The government departments and chambers of trade received support to develop curricula and teaching tools – including teaching and learning materials – for apprenticeships in four trades: hairdressing, sewing, motorcycle mechanics and carpentry.

Generally, the government programmes are for literate young people and include both practical and theoretical components. The WNCB team discussed that young people who are illiterate should not be excluded from the programmes and as a result the government included a functional literacy component for those who need this support to pass the exams.

About 60 youth who had previously been working were given the opportunity to go to school, learn to read and write, and begin vocational training. Besides, the government was supported in setting up a programme for (young) tradespersons who have not completed basic education and do not have any formal trade qualification. Tradespersons must register with the government and after an official visit and assessment of their theoretical and practical skills, they are issued with a diploma.

Community support

Looking back at 4 years of WNCB supported activities, Ambroise not only looks back at the 100 bridge classes that were implemented. He can also count up to 38 classrooms that were actually built in 27 villages in the Nawa region. The communities, through this action, have enabled many children to have access to a quality education that increases their chances for a better life. School attendance prevents these children from being in work situations.

In addition, the programme has implemented a series of community mobilisation activities to support communities organise themselves into local development associations. The capacity of these associations has been strengthened, providing them with financial support for the purchase of education materials not available in the communities. The communities, in return, provided land, wood, gravel, water and the labour needed.