Certified vocational training & market demand focus

Community based vocational training

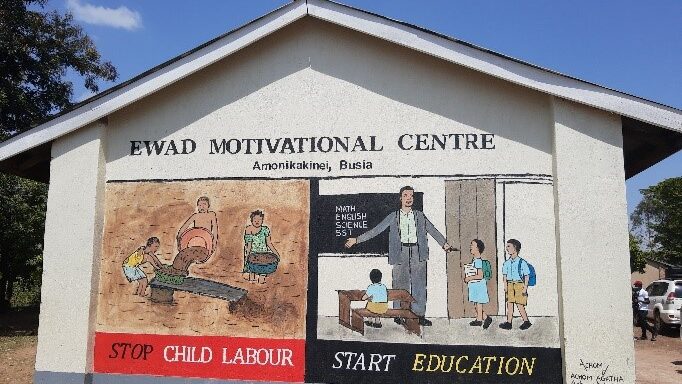

Parallel to the projects in the Karamoja region, WNCB activities were initiated in the Busia region. Richard Kidega, one of EWAD’s project managers, recalls how it all started. “When we started, we conducted a survey among households in Busia. The survey confirmed that one of the key drivers for children to drop out of school and work in the mines was financial constraints, poverty. It also showed that the age range of children working in the mines was from 5 to 17 years. Children from 5 to – let’s say – 12 or 13 years old still have a chance to re-enter normal schooling. For the older children, quite often, that is not possible anymore. They have been out of education for too long. For them we had to find a different solution.”

Looking for an alternative approach for these youngsters, the WNCB programme started with providing vocational skills training. “At first we would send the children to established vocational government schools”, Richard says. “But these schools were really far away. We saw too many dropouts, just because of travel times and the challenges of a boarding situation. Some of the children were young mothers too. For them it was even more difficult.”

Richard continues: “That was when we decided to try and contextualize vocational training in our own communities. In 2020, we established our first community based vocational trainings. We started with reading and writing skills, whilst at the same time trying to focus on locally marketable skills. Having transmitted to community level, we were able to get qualified trainers who had a base in the community. This certainly helped to connect to the demands that existed in the communities. For the teenage mothers, the local training centres made a lot of difference too. They could much easier attend and successfully complete their training, and still take care of their babies.”

Training based on market demands

After the start of the vocational training centres, a growing number of community members started taking an interest in the developments. “A good part of the growing success lies in the fact that we are now organizing training for trades that are really in demand”, Richard clarifies. “We have the flexibility to change from one trade this year to another trade next year, depending on how the demand in the community really is. With established centres this is not possible. You cannot change their curriculum.”

Richard explains further: “In the beginning we started off with all the mainstream courses such as mechanics, driving, tailoring, carpentry, and hairdressing. But quite soon, we found that for some vocations people were not able to use their skills in practice. As a driver, for example, you either need a car, or at least a client with a car. And quite often you need to speak English. It took not more than some brainstorms and assessment sessions to conclude that drivers were simply not needed in our communities. At the same time, we saw so many motorcycles in our villages, many of them in a bad state. That is when we decided to shift from vocational trainings for drivers to trainings for motorcycle maintenance. The same way, we decided to pause our carpentry training for a while. It is a very good course, but at this moment, there are enough carpenters in our communities. We decided to focus on more marketable trades instead, like manufacturing liquid soap and hairdressing.”

Creating a sustainable base

For the vocational trainings the WNCB partners rented a building, providing a learning environment for different departments such as garment (tailoring), hair dressing and catering. For the vocation of motorcycle repair and carpentry separate workshops were found. “We are quite happy with these places”, Richard comments, “but renting a building is something that keeps adding to the costs. Therefore, we are now connecting with community mobilizers and some of our leaders, offering them the opportunity to develop a community business plan for the centre. So, when we are not using the centre, the community can still use the centre for other purposes. This way, we try to make it self-sustainable.”

Another way of enhancing the sustainability and success of the training centres is through the so-called youth to youth peer support. Richard explains: “Initially, we were hiring external people to train our youth. However, during the training we now also keep an eye on the classes to see which students are performing well. When they have reached the working age, we invite them to become trainers. The ones that have accepted, up to now, have received training and proved to be excellent trainers. They have passed through the same situations as the children. They can share their experience: ‘I was there too in the mines, but now I have achieved this.’ At the moment, our trainers for carpentry, motorcycle maintenance, liquid soap manufacturing and hairdressing are all graduates from our own courses. They are role models, really understanding the challenges of the students.”

Vocational skills certificates and mind shift

Looking back at the last few years, Richard sees that a lot of changes have been achieved. “So far, at least 70 percent of the youth we have reached in our vocational trainings, started their adult working life in other sectors than the mines. Some are employed, others are self-employed, some have become trainers in our own programme. Quite a few have moved to other districts because of job opportunities. This was enabled by the fact that the vocational trainings have been certified, officially, by the Directorate of Industrial Training (DIT). That was a particularly important step, giving our graduates recognition for what they have learned and achieved.”