India

No child marriage but education for Manisha

Manisha Kumari, a young girl from Purnadih Mallah Tola village in the Jagdishpur Block Nautan Panchayat (Bihar), is the oldest of four siblings. With her parents working as labourers in Chandigarh, she had to take on the role of caretaker for her younger brothers and sister. After finishing seventh grade, Manisha left school to help out at home.

In the village, WNCB partner the Fakirana Sisters Society (FSS) had established a peer group for girls, and through this group, word spread that Manisha’s parents were considering arranging her marriage. Concerned, the group informed the FSS community mobiliser, who raised the issue with the village chief and a local ward member. Together, they spoke to Manisha’s parents, explaining the risks of child marriage and the benefits of education.

At first, Manisha’s mother didn’t see the need for further schooling, questioning how an education would benefit her daughter. She didn’t see the use in education for girls, as they would not use it after getting married anyway. However, the ward member, Mr. Dinesh Sahni, explained the legal aspects of child marriage and highlighted the positive impact education could have on Manisha’s future. He also spoke with Manisha, encouraging her to think about returning to school.

After reflecting on the conversation, Manisha decided she wanted to continue her studies. She asked the FSS staff to help her re-enroll, and with their assistance, she was soon back in class, joining eighth grade at the local government school. Now, Manisha is happy to be back at school, learning alongside her peers, and looking forward to her future with new possibilities.

She says that if project staff and community members hadn’t spoken to her and her parents about the dangers of child marriage, she would have been married off as a child bride.

Trafficked Sunita now in school

Sunita Kumari lived with her mother, father, two brothers and a sister in Belbanwa village of Miyapur panchayat under Bairiya block of West Champaran district (Bihar). When Sunita Kumari was in the 5th class of primary school, her mother Ramvati Devi and father Shuddha Ram passed away.

With limited options, Sunita moved to Chandigarh with her elder sister, Savita. But after just a month, Savita did something unimaginable: she sold Sunita to a contractor for Rs. 10,000, forcing her younger sister into domestic labour.

When Fakirana Sisters Society mobiliser heard about Sunita’s situation, he immediately went to meet her brother. He encouraged her brother to go to Chandigarh and bring Sunita back to the village, which he did. Together with his aunt and uncle, he brought her back to her home village. Sunita now lives safely with her aunt and uncle.

Upon her return, the Fakirana Sisters Society enrolled Sunita in a sewing center, part of the Work: No Child’s Business (WNCB) programme. Before leaving her hometown with her sister, Sunita was enrolled in school. Now she is learning to sew and will marry at an appropriate age. Sunita’s brother is grateful to Fakirana Sisters Society for changing Sunita’s life through their awareness campaign and other support in their community.

If her parents were still alive, Sunita’s sister would not have sold her to do domestic work in the city. Being a girl, unfortunately Sunita’s position was more vulnerable. If Sunita had been a boy, she would not have been subjected to such treatment and discrimination. Now, she is happy and attends the stitching center daily where she learns new skills.

Vietnam

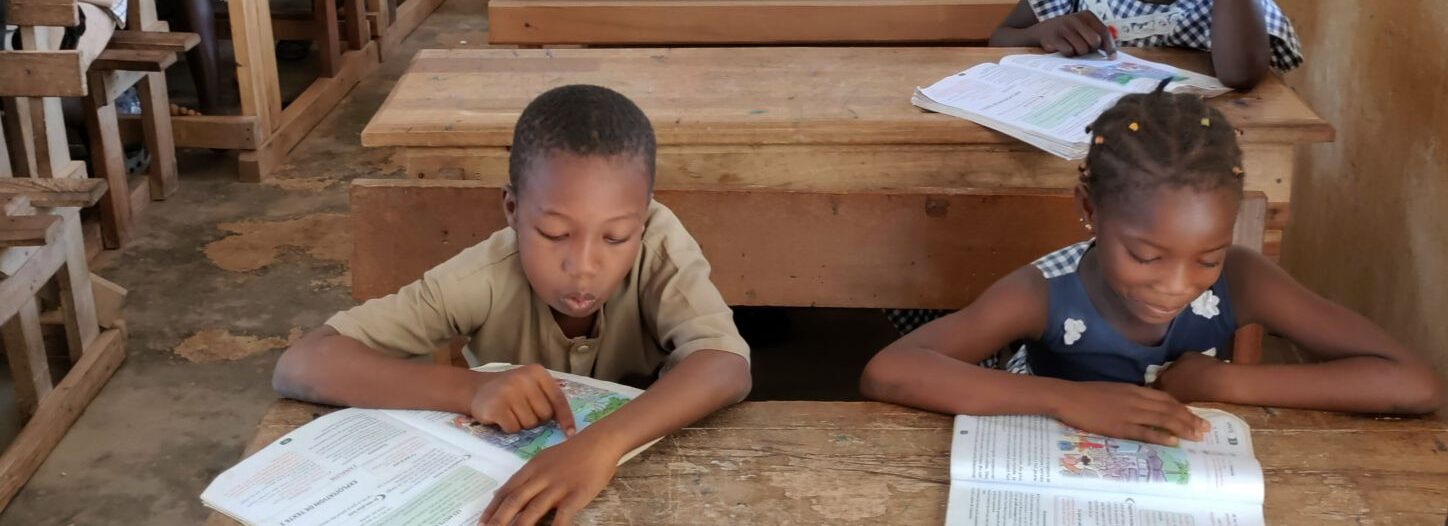

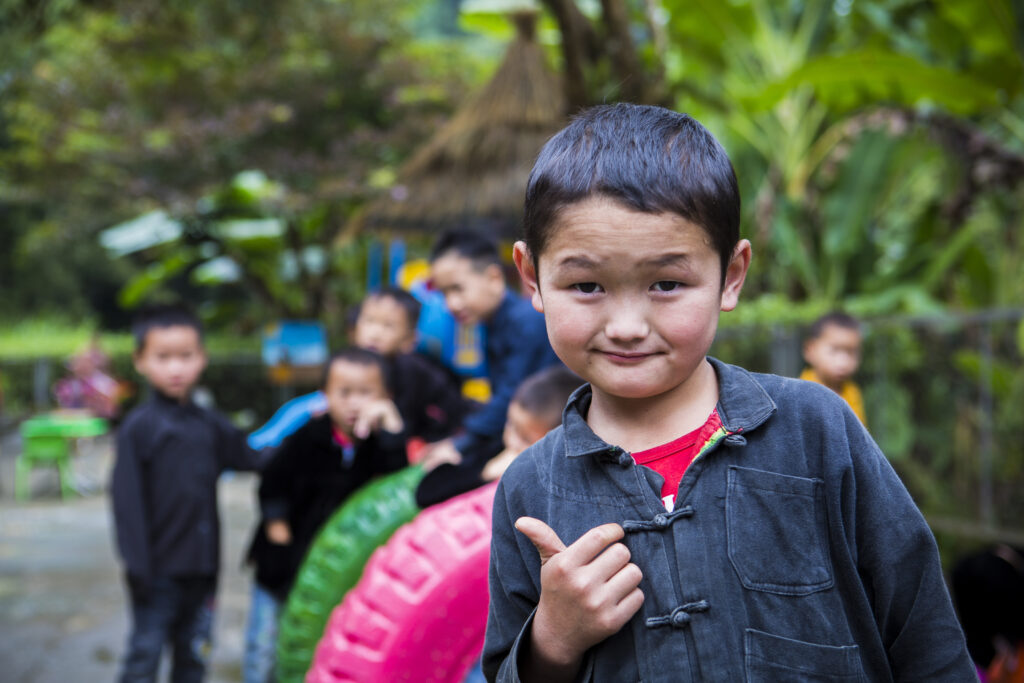

In Vietnam, girls and boys are affected differently by child labour. For example, social or cultural norms and perceptions of gender roles may lead families to prioritise education for boys over girls. In the 13-14 age group, more girls than boys drop out of school. This is because parents place a higher priority on secondary education for boys, and in some ethnic minority communities there is a tradition of early marriage for girls.

Social and cultural norms and perceptions of gender roles also influence the type of work boys or girls do. Boys are more likely than girls to be involved in hazardous agricultural work, such as handling chemicals, using sharp tools or catching fish on boats at night. Girls do domestic work, such as caring for younger children, cooking and cleaning, or doing laundry and other household chores.

Many children in Vietnam who attend school every day also do household chores, ranging from 30 minutes to 4 hours a day. Combining school and household chores is a culturally ingrained phenomenon in the country. Adults see value in children doing household chores to build strength and character. Girls’ domestic work is often in addition to paid work and is rarely recognised as work. Compared to boys, girls are more likely to be involved in multiple tasks. This multitasking drastically reduces their opportunities for schooling and socialising.

Gender inequality norms and practices are also reflected in women’s livelihoods. Their economic opportunities are lacking and their resilience is suffering. Women often have less of a voice in family and community decision-making processes. Poor migrant women in particular are often overlooked in local support systems. This gender inequality and lack of community involvement is one of the root causes of child labour.

Uganda

Lilian’s story

In the heart of Tiira Town Council, Busia District, on the border between Uganda and Kenya in the far east of Uganda, the story of 20-year-old Lillian is a story of resilience and transformation, and illustrates the powerful impact of skills development and financial independence on gender equality. Lillian’s journey began in difficult circumstances. At the age of 16, during the COVID-19 pandemic, she became pregnant and faced severe stigmatisation in her village.

“I was seen as a curse, a disgrace because of my teenage pregnancy while I was still at school and at home. I hated myself,” recalls Lillian. Forced to drop out of school, she turned to gold mining, a physically demanding job, to survive. “It was a very hard time,” she says, describing the grueling work of carrying vats of ore and crushing them into powder while pregnant in the hope of finding gold.”

Her life took a positive turn when Mrs Aguttu Josephine, a community mobiliser trained by WNCB partner EWAD, recognised her potential and the risks she and her unborn child were exposed to. According to Lillian, Aguttu referred her to the EWAD/WNCB project Vocational Training Centre in Tiira for further counselling and rehabilitation. “I couldn’t stand the pain of seeing a child like Lillian carrying a baby in her belly and also carrying loads of ore from deep in the mines to the sluice ponds. It was too risky and very inhumane I’m very happy that she listened to my advice to join the EWAD project,” says Aguttu Josephine.

At the WNCB centre, Lillian recalls that she received training in tailoring. “At the end of about 10 months of training at the tailoring centre, I was able to earn some money by making clothes for people in my community. Because we had also received some financial education, I joined a Village Savings and Loan Association (VSLA),” she explains.

With the support of her VSLA group, Lillian borrowed 150,000UGX (USD 40) to buy sewing materials. After completing her training, she graduated and opened her own tailoring business in Tiira Town. She also ventured into buying and selling Kenyan shoes. Starting with just 150,000 UGX, she now earns an average of (120USD) 400,000 UGX. Lillian’s transformation is not just about financial gain; it’s about the empowerment, independence and willingness to take up work away from the mines that she has achieved. “I can now provide for my family, buy school materials for my siblings and pay their fees,” she says proudly. No longer dependent on the father of her child, Lilian has found peace and the ability to make productive choices in her life.

Her success has had a ripple effect in her community. She is passionate about sharing her skills and opportunities with others, training and employing local women. Her dream is to expand her business, open another shop in Busia town and buy land to build her own house, challenging the stigma in her community that women cannot own land or build their own homes. “I hope that my story will encourage other women to believe in themselves and pursue their dreams, even when times are tough,” says Lillian.

Jordan

In Jordan, our partners worked in East Amman and Za’atari refugee camp. Domestic work is very common in both the Za’atari camp and in East Amman. This type of work is more common among girls and much more hidden; they work long and exhausting hours and are denied basic rights such as access to education and health care, the right to rest, leisure, play and recreation.

Girls in East Amman and Za’atari refugee camp also face the issue of child marriage (between the ages of 12-17). Child marriage forms a huge obstacle to the education of girls, often pushing them into domestic work.

Other reasons for girls in these areas not to attend school, which pushes them into child labour, is a lack of safe routes to school (violence of the way to and from school), the fact that parents don’t value a girls’ education as much as the education of boys and that they choose work over school for their daughters, and strong social and cultural norms that discourage girls from attending school.

Mali

Rokia Sidibé is a 15-year-old girl who worked in gold panning. She comes from the village of Fougatiè and is a member of the village’s youth association. Rokia was identified by Enda-Mali, a WNCB-partner, to participate in a training course for young people to improve her technical skills and help her get out of the gold panning industry.

Working in gold panning is very risky and the profit is uncertain. Rokia used to commute between the community’s gold panning sites and the village’s agricultural work, as well as doing domestic work in the village. “Before the WNCB project, I never went to school and never had the opportunity to attend a training course. But now, in such a short time, I have learned new information and skills and have been doing very well” she says. “The technical training has really improved my skills”.

“Immediately after the training, I wanted to stop gold panning and be with my parents in the market garden to apply what I had learned. I would much rather work in agriculture than go to the gold panning sites all day long with no guarantee of earning enough money to pay for my living. Ever since we finished the training and received financial support from the project, I have been working in the garden like the other young women in the village.

”The garden is collective, but each one has her own beds. This gardening is fun and I ask other young girls of my age to come and work with me instead of panning for gold. I am very grateful to the project for giving this opportunity to the young people of my community. I hope that the project will continue in other villages in my community to give a chance to others who didn’t have the opportunity to attend the training”.