Starting to work in Budhpura

When we started to work in Budhpura and understand the local situation, we concluded that we were going to require a lot of patience. A significant part of the village population came from outside the area and the business context (the stone sector) has a heavy influence on people’s life and livelihoods, meaning that the people in Budhpura have different characteristics in terms of needs, aspirations and developmental priorities. The conclusion – after understanding the context – was that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy would not work. The area-based approach, however, proved to be a useful one in this challenging context, providing us with a space to adjust elements of our planning and action, and leading to sustainable results.

Tailor-made approaches and strategies

Most labourers in Budhpura belong to the unorganised sector, which gave us limited space and means to intervene and negotiate. The space for intervention was also small due to the practice of advance payments, which minimises workers’ opportunities to negotiate with their employers. Workers themselves do not feel they have any space or possibility to improve their situations.

Community mobilisation was challenging, due to the different cultures of migrant families and the labourers’ poor socioeconomic situation. It required a lot of time, and we began by just talking to people. Manjari decided to start working with children first, by orienting them to schools instead of cobble-making. The first initiative for mobilising children was through motivation centres and education. Motivation centres are places where children are supported outside of school, with a library, tuition, sports activities, and training on active learning methodologies, all with the aim of mainstreaming children into formal schools. We started with motivation centres at workplaces, specifically focussing on the children that accompanied parents to work in the cobble yards and mines.

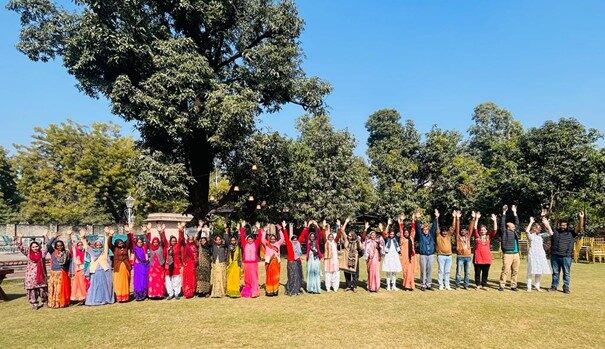

Manjari also started to work with women. We began by organising events with women so they could get together and talk to each other. This led to more of a feeling of sisterhood and support among the women. Manjari also supported the establishment of women’s Self Help Groups (SHG), which resulted in interaction between women from the different social groups in Budhpura. They learned that they face the same challenges. Women today have more interaction with women from other caste groups, in comparison to men.

Working with men in Budhpura was more difficult. Men mainly meet at the workplace, and have little time to mingle on weekdays as they work long days. When returning from the workplace they might stop off at a wine shop, and sometimes stay there to drink together. We joined them there and talked to them in the evenings. When we discuss the issues in small groups, at tea shops or door to door, there is always a good response.

In establishing the Child Labour Free Zone approach, Manjari conducted a range of activities at community level: community mobilising and strengthening community organisations; financial support, linking families to government schemes, and supporting the most vulnerable families with alternative livelihoods; improving quality education by supporting formal schools and interventions outside schools (library, tuition centres, sports activities) and training on active learning methodologies, and; mainstreaming children in formal schools. With regard to improving adults’ working conditions the following interventions have been set up: organising workers into workers’ groups, trainings on labour rights, health camps for workers, and dialogue with businesses in the supply chain.

Working with the business community

Manjari had quite a negative reputation among the business community in the first few years. Cobble traders and yard owners were afraid that Manjari’s interventions would harm their businesses. Engaging with the cobble traders and building trust required a lot of time, before the negative impact of child labour could eventually be discussed. In the period from 2017-2019 Manjari, with support from ARAVALI, successfully engaged with the cobble traders’ association. The association became actively involved in monitoring yards where cobbles were cut and packed for export, to ensure that no children were working. The association set up a system of fines for any members found to making use of child labour. After a change of leadership in the association in 2021, the associating stopped monitoring child labour and ceased to engage with Manjari. The increased shift in production from cobble yards to home workers started in 2021. To address child labour in home work, Manjari’s community mobilisers strengthened engagement with families in the different hamlets of Budhpura as well as strengthening the dialogue with exporting companies.

Manjari continues to engage in dialogue with the local business sector in Budhpura, with support from ARAVALI. Under SFNS, of which Manjari is a member, ARAVALI brings together stakeholders in the sandstone supply chain at state level in Rajasthan. Manjari and ARAVALI also engage with international companies through the co-operation with Arisa in the Netherlands.

Expanding the work

Under WNCB, Manjari works with a fellowship programme in which fellows in other geographical areas in Rajasthan’s stone sector (marble, limestone, red sandstone) are trained to adjust the area-based approach to their own context. The fellows are based at NGOs/CBOs, a women’s credit bank and a worker’s union. Linking and learning between the fellows, Manjari and other NGOs/CBOs is part of the programme.

There are now twelve SHGs that have been set up and trained by Manjari. Manjari is focusing on strengthening women workers and, in the long run, establishing women’s labour groups in Budhpura. A group of women labourers in Chechat are ready to create a union (as part of fellowship programme under WNCB Rajasthan). Manjari organised linking and learning between these groups to enable them to take next steps and responsibility for changes.

Read the story of Sunita, a female cobble yard owner